Climate neutrality in sight for California's dairy and beef industries

Mitloehner Lab at UC Davis makes case in fight against climate change

One percent a year. If the California dairy sector can reduce its methane emissions by that amount, it could reach net-zero warming in a decade’s time.

That’s just one of the promising assertions in “Rethinking Methane from Animal Agriculture,” a recent peer-reviewed paper from researchers at the University of California, Davis.

New white paper maps path to climate neutrality for beef and dairy sectors

“When it comes to greenhouse gas emissions, what is of concern is the warming they cause that fuels climate change,” said author Frank Mitloehner, an internationally renowned expert on animal agriculture and its relationship to air quality.

Mitloehner, who also runs the University of California’s CLEAR Center, explained that methane is not a stronger version of carbon dioxide, as the conventional metric GWP 100 would suggest. It is an altogether different gas that needs to be measured and studied as such.

“Methane is a strong pollutant, but it warms our planet differently than carbon dioxide because of its short lifespan. For cattle industries, where methane is the primary greenhouse gas, we can stop them from contributing additional warming to the atmosphere with relatively small year-over-year reductions in methane,” he said. “Cattle industries can absolutely stop contributing to additional climate change, and in California, they are well on their way to doing so.”

“Cattle industries can absolutely stop contributing to additional climate change, and in California, they are well on their way to doing so.” - Frank Mitloehner

What Mitloehner is getting at is net-zero warming. Also known as climate neutrality, it happens when a sector reaches a point at which its emissions are no longer contributing additional warming to the atmosphere.

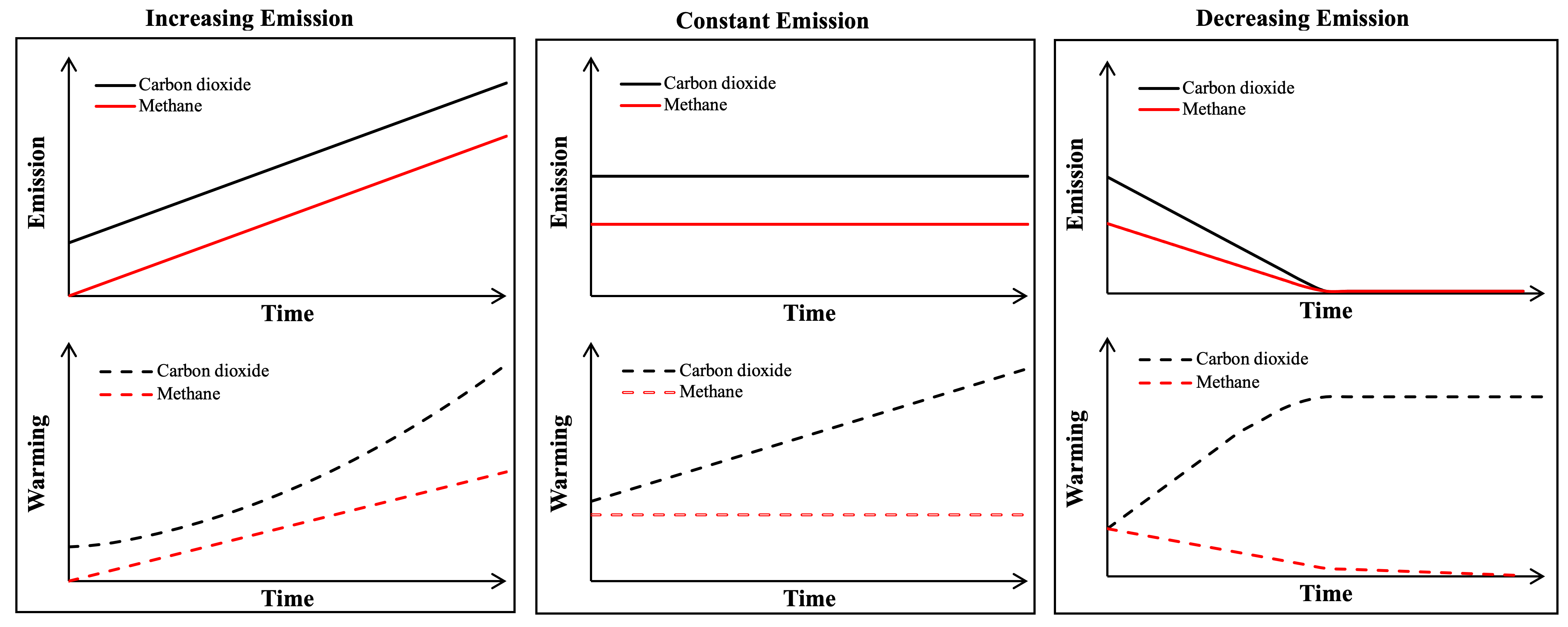

For methane-intensive sectors such as beef and dairy, net-zero warming can be achieved by holding emissions near constant. That’s because methane is a short-lived greenhouse gas that’s destroyed after 12 years. If emissions remain relatively flat for 12 years or more, what’s emitted today is simply replacing 12-year-old methane that’s being destroyed at the same time new methane is being emitted.

As an aside, that’s not so for fossil fuel sectors such as transportation and industry, which primarily emit CO2. The most plentiful of our greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide is a long-lived climate pollutant and a stock gas that has been accumulating in the atmosphere – and warming – for thousands of years. Without a doubt, the goal of climate neutrality is more daunting for carbon-intensive fossil fuel sectors. They have to reach net-zero carbon to curtail the increasing warming they’ve been causing year after year. And given humans’ penchant for burning fossil fuels, that’s a tall order.

Managing what we measure

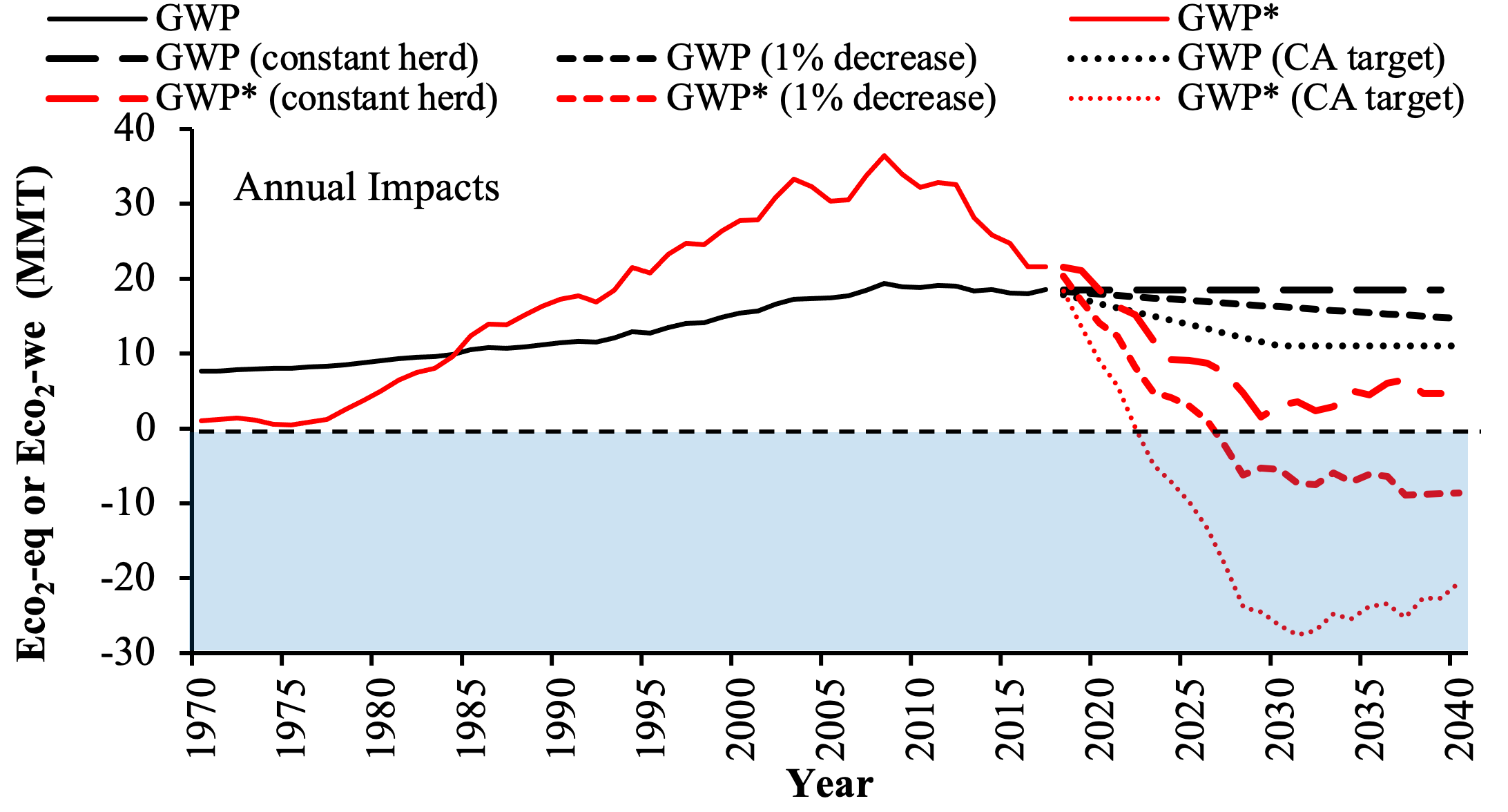

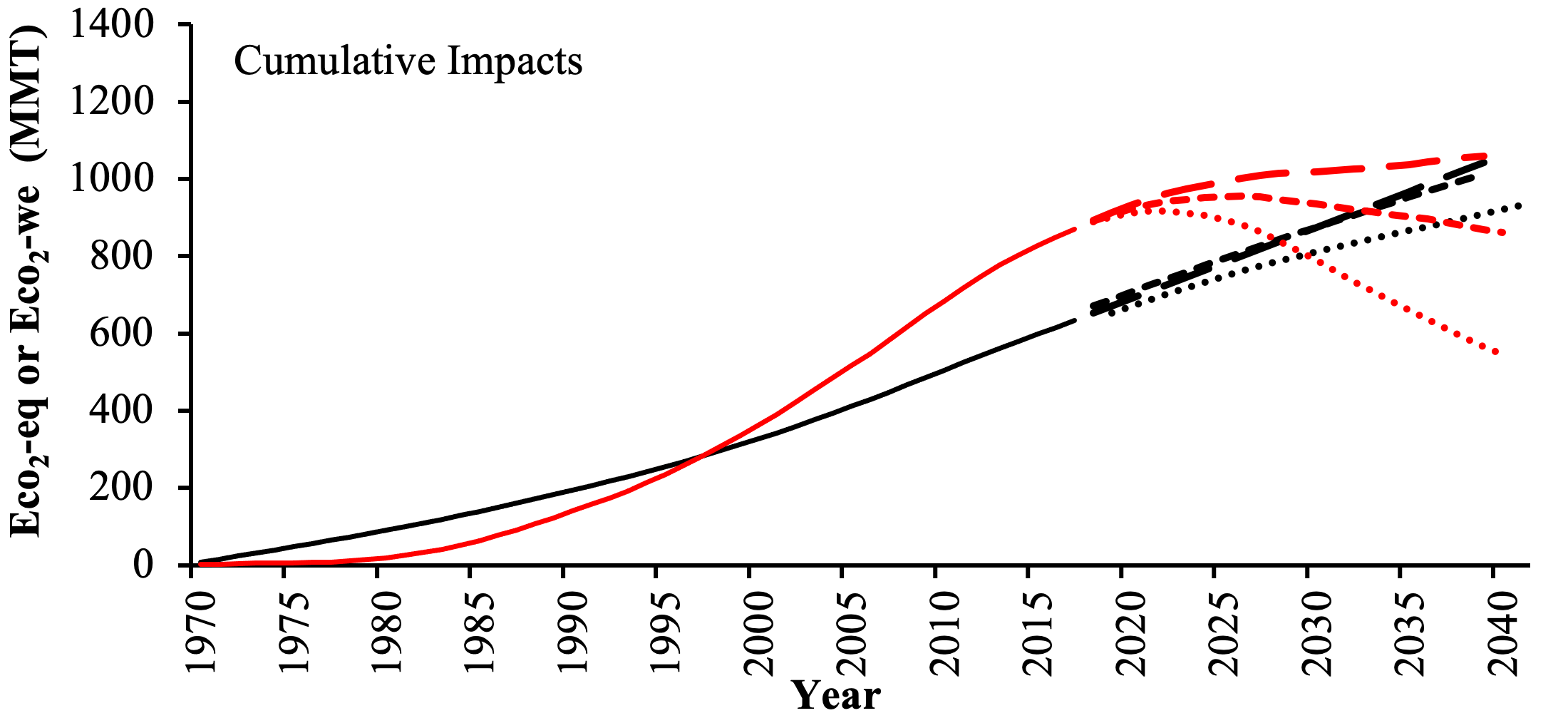

When it comes to measuring methane and supporting the cattle industries’ quest for climate neutrality, the paper makes a compelling case for the adoption of a newer metric known as GWP star or GWP*. Developed by scientists at Oxford Martin School, it builds on and improves upon the older, widely accepted system known as GWP. Instead of converting each greenhouse gas to a carbon dioxide equivalent and giving it a warming value over a 100-year period, GWP* takes into account how each gas behaves in – and thus warms – the planet.

“GWP* is a better way to measure methane’s impact on our climate, because it considers not only emissions but atmospheric removal. The gas lasts for about 12 years. After that, it is broken down into carbon dioxide and water,” Mitloehner said.

Animal agriculture can be part of the solution

As part of the biogenic carbon cycle, cattle consume carbon from the plants they eat, which they captured from atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis. Plants that are undigestible by humans are consumed by farm animals, which upcycle the cellulose to food for people. In the case of cows and other ruminant animals, methane is emitted as a byproduct of their digestive process, which is broken down into CO2 in the atmosphere after 10 years and the cycle begins anew.

Methane from animal agriculture is continually being recycled in this way; previous emissions are being destroyed, as sources emit it. If emissions remain constant, there is no added warming from livestock as what is . If emissions increase, warming increases accordingly. And perhaps most stunning is that if emissions are reduced enough, warming can be reduced. In the third scenario, animal agriculture becomes climate negative, as it can help pull carbon out of the atmosphere.

We’re on the way

In about 50 years’ time, the herd sizes for beef and dairy cattle have decreased by 30 percent and 46 percent, respectively. The methane emissions from U.S. cattle was 27 percent less in 2017 than the 1975 level.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture’s statistical database, total direct greenhouse gas emissions from U.S. livestock have declined 11.3 percent since 1961, while livestock production has more than doubled. This massive increase in efficiency and decrease in emissions have been made possible by the technological, genetic and management changes that have taken place in U.S. agriculture since World War II. Specifically, these include: efficiencies in reproduction; better health, brought about in part by vaccinations and advances in health care; the application of “high-merit” genetics; and more energy-dense diets.

As a result, animal herds are at an historic low in the United States without a corresponding output level. For example, in 1950, there were 25 million dairy cows in the United States. There are 9 million presently, but today’s herd produces 60 percent more milk than their ancestors did. Put another way, the carbon footprint of a glass of milk is two-thirds smaller today than it was 70 years ago.

“More efficient methods of farming, such as those developed and adopted by U.S. farmers since the 1950s are critical to meeting worldwide demand for meat and dairy while we work to get a handle on climate change,” Mitloehner said.

California is taking a leadership position in the United States by setting aggressive targets for emissions reductions. For example, through Senate Bill 1383, the state is challenging the dairy industry to reduce 40 percent of methane emissions (based on the 2013 level) by 2030.

Dash-dotted lines represent the GWP and GWP* results when the methane emissions meet California’s mitigation target.

As the sector rises to the challenge, GWP* shows that level of reduction will allow California’s dairy industry to achieve climate negativity – no additional warming – within five years.

As exciting as that prospect is, Mitloehner warns it is not the be-all and end-all to the problem of global warming.

“It’s not a get-out-of-jail-free card,” he said. “Methane from all sources has caused warming, and that props up historical warming. But we nevertheless have a huge opportunity here if we stop for a minute to measure it and understand it better and reduce it for real.”

Is GWP* really 'fuzzy math?' You decide.

Has the beef industry landed on a metric that finally gives it a rosy glow?

Media Resources

Please contact Joe Proudman at jproudman@ucdavis.edu for media inquiries